In a new study, Suddha Sourav, Ramesh Kekunnaya, Brigitte Röder, and other scientists from an Indo-German lab report that sound interferes with the earliest visual cortical processing in sight-recovered individuals born with reversible congenital blindness.

The human brain has a remarkable ability to adapt based on the available sensory input. If one of the senses is missing, the remaining senses often compensate for the loss. People who were born blind, for example, have been reported to have enhanced hearing and touch. At the same time, their visual cortex shows permanent changes, often for the rest of their life, even when sight is restored (e.g., through cataract surgery). In fact, each week of delay in cataract surgery after birth reduces the attainable visual acuity, suggesting periods of remarkable and malleable neural circuitry development early in life, where the brain and its functions begin to refine shape.

The brains of permanently blind people have been reported to exhibit widespread crossmodal activity. Here, non-visual information, for example through hearing or touch, activates those parts of the brain that are typically mapped to the visual cortex. Interestingly, compared to permanently blind individuals, such activation is modest in individuals who had their sight restored after a period of reversible blindness. Thus, researchers have hypothesized that despite the remarkable ability of the brain to process visual information after sight restoration, neural routes underlying crossmodal activity might not completely retract after sight recovery.

A new study published in the journal Communications Biology aimed to investigate whether simultaneous auditory signals would interfere with visual processing after sight recovery. The study was conducted by an international team of researchers, which included Dr. Suddha Sourav, Prof. Brigitte Röder, and others from the University of Hamburg, in collaboration with Dr. Ramesh Kekunnaya from LVPEI. The study included 14 participants who were born blind due to bilateral congenital cataract but recovered sight after surgery (CC group). In addition, 15 participants, who had late onset cataracts and surgically recovered sight, took part in the study. For both groups, typically sighted control participants matched for age, sex, and handedness were tested as well – a total of 58 participants.

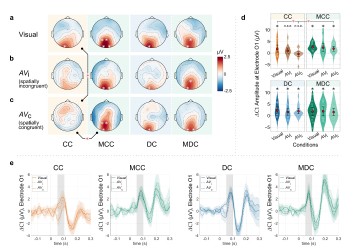

The participants were exposed to visual stimuli either presented alone, or with simultaneous sound bursts. The sound bursts could come either from the same or a different side with respect to the visual stimuli. For visual stimuli presented alone, all groups showed robust early visual cortical activation (replicating the results from a previous report by the same group). But, when sounds were presented along with visual stimuli, the earliest, stimulus-driven visual cortical activity (< 100 ms) was suppressed in the CC group—and not in any of the other groups. This suppression was also spatially specific to the same side as the visual stimuli. These results indicate that atypical crossmodal brain networks are not completely lost after sight recovery but coexist with spared visual networks. The results are important for planning optimal rehabilitation strategies for individuals who recovered sight after a congenital period of blindness. They might be more susceptible to interference by concurrent auditory stimulation.

‘Previously we could demonstrate that the visual cortex of humans who receive treatment for congenital cataracts, learn to “see” after surgery,’ notes Dr. Suddha Sourav, a neuropsychology researcher at the University of Hamburg, Germany, and the first author of this report. ‘Here, we found that sound can suppress the earliest visual processing in people who regained sight after being congenitally blind – opening the challenge to specially adapt visual rehabilitation measures for this group.’

Citation

Sourav, S., Kekunnaya, R., Bottari, D., Shareef, I., Pitchaimuthu, K., & Röder, B. (2024). Sound suppresses earliest visual cortical processing after sight recovery in congenitally blind humans. Communications biology, 7(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05749-3

Photo credit: Figure 3 from Sourav et al.