A new paper by Drs Swati Singh and others from LVPEI, and Prof Dr Friedrich Paulsen from the Institute for Clinical and Functional Anatomy, Germany, explores changes in lacrimal reflex secretions depending on the presence or absence of obstructions to drainage through the nasolacrimal duct.

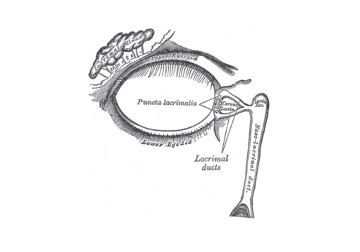

Human tears are a stable fluid made up of water, proteins, lipids, and mucins that form a film over the eye. The health of the eye is tightly linked with the optimal supply and drainage of tear fluid during one’s lifetime. Under-supply of tear film or its instability can result in dry eye disease that damages the ocular surface. Tears are primarily produced by the lacrimal gland (tears are lacrima in Greek), positioned up and towards the ear in each eye, and secrete a continuous film of tears that coats and lubricates the ocular surface. Once tears traverse the eye’s surface, they collect near the inner corner of the eyelids, towards the nose. Here, the tear film is drained out into the nose through the nasolacrimal duct where many fluid components are re-absorbed into the blood.

Tear outflow also results as a reflex—it reflects the state of the world, and the mind. Our ability to produce tears and drain them is a dynamic system that responds to neurosensory feedback. A dust mote in the eye, the fumes from a chopped onion, or a sad film (a ‘tear-jerker’) can increase tear production resulting in watery eyes and a runny nose. But does the drainage and the subsequent fluid re-absorption also feedback and inform tear production? In patients with a condition called Primary Acquired Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (PANDO), the nasolacrimal duct is inflamed, obstructing the outflow—all other aspects of the lacrimal system are healthy. A test for PANDO measures their tear meniscus—the convex bulge of the tear fluid accumulated in the eye— which is higher than normal in such patients. Other tests like the tear break-up time, and the Schirmer 1 test to evaluate tear production should be close to normal. In such patients, would their obstructed tear drainage lead to reduced tear secretion?

A new study in the British Journal of Ophthalmology by Drs Swati Singh, Saumya Srivastav, Nandini Bothra, and Mohammad Javed Ali from LVPEI, and Prof Dr Friedrich Paulsen, Institute for Clinical and Functional Anatomy, Germany examines this question. Their study included 30 participants (24 female) with unilateral PANDO and obstructive epiphora (excessive tears due to poor drainage). The key idea of this study was to compare mean tear production between the asymptomatic eye and the obstructed eye in each participant. Eyes with PANDO had higher mean tear meniscus. All other measures showed similar values between the two eyes.

The study found a significant reduction in the mean tear flow rate in the eyes affected by PANDO, when compared to the asymptomatic eyes (0.8 vs 0.99μL/min). As all other measures were similar, the study was able to rule out Dry Eye Disease as a cause for this tear flow reduction. The results from this ingenious study strengthen the possibility of feedback between the drainage ducts and the lacrimal gland’s secretory pathways. With this established, the exact modalities of this feedback process need to be figured out.

‘Understanding the physiology of tear production and drainage is crucial for managing the disorders of lacrimal system,’ said Dr Swati Singh, consultant ophthalmologist at LVPEI, and the corresponding author for this paper. ‘Lacrimal gland and lacrimal drainage system are anatomically located far apart yet communicate with each other in a beautiful manner. The ongoing work would explore this relationship for patients with watering despite a patent lacrimal system.’

Citation

Singh S, Srivastav S, Bothra N, Paulsen F, Ali MJ. Lacrimal gland activity in lacrimal drainage obstruction: exploring the potential cross-talk between the tear secretion and outflow. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023 May 4:bjo-2022-322577. doi: 10.1136/bjo-2022-322577.

Photo credit: Nasolacrimal duct; Gray’s Anatomy, Plate 896; Public Domain.